I didn’t grow up listening to jazz. My dad was a fan of The Platters, Elvis Presley, Roy Orbison and Bobby Vee, a lesser known singer who sounded like Buddy Holly. But he did adore long-play records and our living room always had a “Hi-Fi”, sort of a buffet- looking box of a cabinet with an internal phonograph submerged under a large wooden lid. The speakers were disguised behind glittery gold fabric screens located on the lower left and right corners of said box. Next to the turntable it had big push buttons, like a 1950’s car radio, and a huge volume knob. And a father’s small record collection could easily be stored in an opening above the controls. He was too young and working class for Sinatra and barely too old and conservative for the Beatles. As I grew older though I noticed something inspiring about his record collection – it was eclectic, diverse: Mahalia Jackson, Johnny Mathis, the Lettermen, a few classical records, Glen Campbell, Chet Atkins, the Ventures, Slim Whitman and even a jazz standards album from Willie Nelson called Stardust.

When I was twelve, I bought my own first album at Sears, Eagles: Their Greatest Hits ’71-’75, which is still in my collection. On the back cover it has the letters of my name scrawled with a blue Bic in the same font used on the record’s artwork. It was the beginning of me mirroring my dad’s love affair with vinyl, although he would have never desecrated the cover art work with an ink pen. He had taught me how not to touch the grooves with your oily fingertips, but to carefully hold the outer edges and make certain you blew the dust off the stylus before you dropped it on any side of any record.

And from the start, I also had a range in what I appreciated musically, however succinct the variation. I had already learned to enjoy my dad’s records. My introduction to the Beatles was through his Chet Atkins Picks on the Beatles. And Roy Orbison’s 1961 cut time Blue Angel and the crown jewel Only the Lonely still knock me over today. One of Dad’s brothers, my uncle Rodd, introduced me to Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons on a trip to visit his family in Los Angeles, from whence we had moved to Georgia a few years prior. By the age of ten I was listening to Casey Kasem’s Weekly Top 40 on WWID Wide 107 where we lived in Gainesville, the chicken feed capital of the state. A 4-hour commitment, I would transcribe the entire list as Casey counted down the songs every weekend. I still recall the first time I heard Carry On Wayward Son by Kansas and More Than a Feeling by Boston coming through those Hi-Fi speakers. And Nights on Broadway by the Bee Gees and Detroit Rock City by Kiss and Fire by the Ohio Players. Even now if I hear Ambrosia’s How Much I Feel I get freezing chill bumps all over. Okay, so it wasn’t yet a deep appreciation of tonal diversity, but at least it wasn’t a narrow one.

And so, although I never listened to a jazz record from beginning to end until I was well into my twenties, I did learn from an early age to appreciate a varied taste of musical flavor. Dad gave me that gift. And he was never racist or snobby or goody-goody about other styles. To him, it was a universal language and music contained the ability to obliterate barriers and give people a common language to appreciate each other’s plight in this condition we call human. I still remember bringing home Judas Priest’s Screaming For Vengeance during my angry teen years and Dad came down to my room, laid on my bed and listened to You’ve Got Another Thing Coming. From what I could tell, he understood why I was attracted to it and he never scoffed or lectured or rolled his eyes.

I think Dad’s Chet Atkins records, more country than jazz, primed me for how an artist could take any song, even a Lennon-McCartney hit, and reinterpret the melody’s unique way of expressing a feeling or experience without employing a single lyric. Similarly I took the long way and found classic jazz through reinterpretations of the originals. It all started by my listening to the solo guitar recordings of the L.A. studio cat Larry Carlton who I’d previously heard on Steely Dan’s Aja and television show theme songs. In my early twenties, I was a self-taught, mediocre guitarist and I became enamored with his version of the 1960’s surf song by Santo & Johnny called Sleepwalk. I actually learned his version note for note and played it in a small talent show, one of my very first public performances on the guitar. In 1986 he released a live album entitled Last Nite which included, unappreciated by me at the time, the 1959 Miles Davis classic So What. This is what slowly pried open the flood gates for me, a little here and a bit there. Then I bought a CD, one of my first, of a jazz fusion concert published by GRP Records which featured pianist Dave Grusin, guitarist Lee Ritenour, flutist Dave Valentin, drummer Carlos Vega, bassist Abraham Laboriel and Diane Schuur, a blind vocalist with tremendous power. Then Schuur’s records later introduced me to Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughn, Dinah Washington and Billie Holiday, all jazz masters by then deceased. In 1989, I started attending UTK architecture school as a 24-year old married student. There were many late nights spent working on design projects accompanied by my small collection of jazz CDs including Dave Grusin’s The Gershwin Connection. And it was in downtown Knoxville where I bought tickets on the front row to see Larry Carlton, with Abraham Laboriel on bass, at the Tennessee Theatre. I had yet to discover the original source of all this great material I was learning to love, only being introduced through the vehicle of these contemporary interpreters. But sometimes wading in at the shallow end can have its advantages.

As I grow older now, much older, I have come to appreciate the jazz genre immensely. It might have something to do with my creative career where I need something to fill the silence without jamming my brain with lyrics and textual ideas, although some of the records I adore do have singing. But moods, melodies, swinging grooves and flatted sevenths or major ninths are powerful background tools when you need to focus and solve problems. And sometimes just getting up in the morning and sitting still for a half hour with a cup of coffee and Pat Metheny playing through the Cerwin Vegas is peace for the soul just before running out to battle the world.

That’s more than enough about me though. If you are ready to listen to something new, something to cut across the old sonic paths you’ve trained your ears with over the years, then let me recommend you give jazz a try. But where would you start? There are, after all, hundreds of thousands of jazz recordings. This uniquely American style which started in New Orleans and Chicago has had over 100 years to develop and its catalog can be overwhelming. Not to worry, friends. I’d like to get you to the source much sooner than it took me to discover it all. Following is a jazz primer to introduce you to some of the best albums, in my subjective opinion of course, in jazz history. Now let me reiterate, these are my favorites. If you check any “greatest jazz albums of all time” list, you will find records by others such as John Coltrane and Charlie Mingus. But those “bop” a bit too hard for me. Remember, this is just a primer, if you will; a starting point, an introduction. I hope it will open up new valuable avenues of listening pleasure and lead you to places you’ve yet to experience. If nothing else, I hope some of these recordings put either a smile on your face, a clap in your hands or a twinge in your heart. Also, as a tool, I’ve created a playlist in Spotify with all of these albums included. A link is listed below. Are you ready? Here we go!

Kind of Blue – Miles Davis, 1959

Check about any “greatest jazz albums” list and this will be at the very top of nearly every single one. It is supposedly the best selling jazz album of all time. The absolute beauty of this album is the improvisational skill in which these mere five tracks are so eloquently crafted. According to history, Davis and his group made this recording with no rehearsal, but only notes he had scribbled down for them about melody and scales. Only one song was actually recorded in one take, but it’s still a testament to the beauty of the record that it was completed in only two sessions at Columbia’s 30th Street Studio, where the Broadway cast recording of West Side Story (another one of Dad’s albums) and later Pink Floyd’s The Wall were also recorded. This album has also been cited as influential to countless jazz and rock musicians. John Coltrane is present here too, mentioned earlier, as is Bill Evans, listed below.

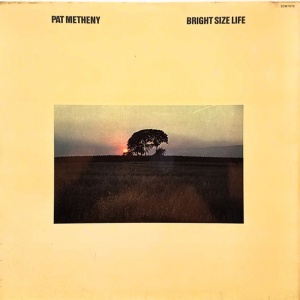

Bright Size Life – Pat Metheny, 1976

Guitarist Pat Metheny recorded his debut album at the ripe age of 21. It also features 25-year old bassist Jaco Pastorius and 28-year old drummer Bob Moses, all now legends in jazz lore. The music performed by this young trio is unbelievably mature, intricate and at the same time gorgeous. The opening track is a study in jazz guitar 101 and jaw-dropping beauty which sets the tone for most of the remainder of this masterpiece. The very last track is the only one I tend to skip in the mornings as it is the only moment where their maturity gives way to a youthful, look-what-we-can-play feat of scales and chaos. Aside from such a small complaint, I can’t get enough of this recording.

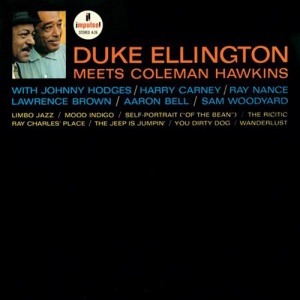

Duke Ellington Meets Coleman Hawkins – Duke Ellington & Coleman Hawkins, 1963

Duke Ellington Meets Coleman Hawkins – Duke Ellington & Coleman Hawkins, 1963

No roster of jazz highlights would be complete without a Duke Ellington record. Born in 1899, he had one of the most prolific, innovative and influential careers of just about anyone in the history of American music. Coleman Hawkins was a tenor saxophonist who took the instrument from one that had previously been considered a non-jazz instrument to one of respect and impact. This recording doesn’t have Ellington’s entire jazz orchestra but rather choice musicians pulled out to create a sound that is more open, and which creates plenty of space for Hawkins to fill with his incredible sound. This record swings almost all the way through and then ends on a tender violin-laced ballad called Solitude. Considered by some to be one of the best albums of both of these artists’ lexicons, it is a must-hear album for anyone learning to appreciate various forms of the jazz idiom.

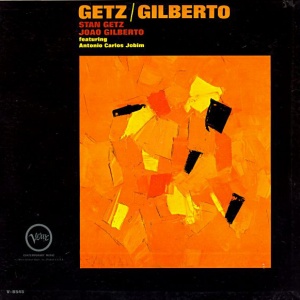

Getz/Gilberto – Stan Getz & João Gilberto featuring Antônio Carlos Jobim, 1964

Less is definitely more. Another of the best-selling jazz albums of all time, this record introduced Brazilian bossa nova to the US and won a Grammy for Record of the Year in 1965. It is also one of my personal favorite albums, period, regardless of style. Part of its magnificence is the warmth found in the marriage of the reedy delivery of Getz’s saxophone with Gilberto’s latin guitar chord progressions and rhythms, as well as the minimalism of Jobim’s piano fills. When I play this record, I can feel the stress leaving my pores. It also features vocals from Gilberto’s wife Astrud on two tracks, soft and hush, like a precursor to Sade two decades later. Probably the best thing I love about this record is its 1960’s essence. I close my eyes and I’m a kid in southern California again, long before my world got complicated and pressured.

Ella and Louis – Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong, 1956

Anytime you throw contrasting textures together, each tends to emphasize the other’s strengths. So when you place one of the clearest and controlled female vibratos of the 20th century adjacent to one of the scratchy-ist, signature male vocal stylists in history, allowing him to pepper into the mix some of his famous spit-filled trumpet lines, and finally you back it up with the groove of the Oscar Peterson Trio (see below), you end up with one of the most complementary albums of all time. These were in fact their interpretations of popular ballads. This record feels like you’re right in the middle of a 1950’s Grant/Hepburn film set in New York City. And Stars Fell on Alabama is a must-hear-before-you-die track.

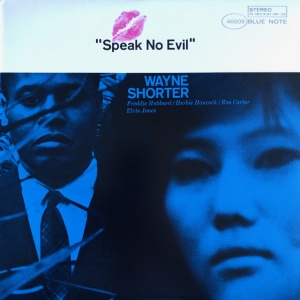

Speak No Evil – Wayne Shorter, 1965

Speak No Evil – Wayne Shorter, 1965

When this album was originally released, it was lost in the saturation of Shorter’s other releases in ’64 and his role in Miles Davis’ band at the time. Years later it rose to the top of the heap as probably the best of his career. The sound of this record captures the feel of a smokey jazz club in the city on a hot summer night. And many of Shorter’s sax parts are doubled by trumpeter Freddie Hubbard, sort of like a Beatles lead vocal. That sound is so distinctive you’ll think you’ve heard the record before. Also featured on the record is a young pianist named Herbie Hancock, another of the biggest producers of the past 40 years.

Night Train – Oscar Peterson Trio, 1963

Night Train – Oscar Peterson Trio, 1963

Trains have a long history in folk, jazz and rock styles. There’s a reason for this. America has had a love affair with this mode of transportation from the beginning – the excitement of new adventures and destinations while enjoying a front row view of our beautiful landscape. Then there are the musical similarities: the rhythm of the connecting rods moving the giant wheels, the power of the steam engine and the billowing smoke trails – a lot like a jazz trio in fact; drums, bass and in this case, piano. I use one verb to describe this record: it feels. Whether it’s the groove of the opening title track, or the longing of Georgia On My Mind or the reserved pace of Bag’s Groove, the Canadian pianist and his group speak with authority, interest and honesty and if they don’t make you feel what they are laying down, I have no cure for your callous ailment.

Never Stop II – The Bad Plus, 2018

Rolling Stone magazine ranked this album #1 in their list of 2018’s top 20 jazz albums. The Bad Plus is a Minneapolis jazz trio who reside right in the middle of our modern-day era. But they are unbelievably apt at creating completely original music within the language of traditional jazz. Many of their albums contain jazz takes on some of the most well known rock/pop tunes ever made like Rush’s Tom Sawyer, Tears For Fears’ Everybody Wants to Rule the World and Nirvana’s Lithium. But this record, just like 2010’s Never Stop is comprised of all original tunes. It is simultaneously intricate and yet simple, sometimes breakneck and moments later serene. Some of the meters are dramatic and the piano runs blinding. Overall, it’s an incredible treat in which to expose your eardrums.

Midnight Blue – Kenny Burrell, 1963

One of the best jazz guitar albums, again my opinion, ever made. The one word to describe this record is already listed in the title – blue. Now I don’t mean depressed or sad. I refer instead to the musical scale present throughout the recording. Even blues guitar legend Stevie Ray Vaughan recorded a rendition of the opening track Chitlins Con Carne if that tells you anything. The result is an album of extended laid back cool vibe. There’s nothing more to say, just give it a serious listen. One of the highlights is the very last track called Saturday Night Blues which features legendary saxophonist Stanley Turrentine.

Waltz for Debby – Bill Evans, 1962

Waltz for Debby – Bill Evans, 1962

This album is a live recording from 1961 which took place at New York’s Village Vanguard, a legendary jazz venue and the oldest in the city. One of Evan’s (see Kind of Blue above) most celebrated records, you can even hear patrons’ nonchalant chatting during extra quiet parts and clapping between tracks. As if you were sitting there yourself, it’s intimate, personal – the title track was written for Bill’s niece – and soothing. There are a few instances of drummer Paul Motian, another jazz giant, and double bassist Scott LaFaro having some fun at appropriate moments, but the universal sound here is a monolithic unit creating a stunning soundscape for generations to enjoy. Sadly, LaFaro was killed in an automobile accident only ten days after the performance. Yet another reason this record is so moving.

You Must Believe In Spring – Bill Evans, 1981

For this primer, I tried to span as many artists as possible for the sake of variety. But for Evans, I would be remiss to leave out another of his masterpiece recordings as both are two of my darling, quiet, jazz piano trio works of art. The beauty of this record begins on the first line of the first song and flows through to the last groove. Evans recorded this album in 1977, his last before his death in 1980. It also features the notable Theme from M.A.S.H. Featured prominently are Puerto Rican double bassist Eddie Gomez and Eliot Zigmund, a session jazz drummer who has played with legends like Stan Getz (see above) and Chet Baker.

Sinatra – Basie: A Historic Musical First – Frank Sinatra & Count Basie, 1961

Sinatra – Basie: A Historic Musical First – Frank Sinatra & Count Basie, 1961

Once again, place two distinctive, iconic stylists together and just see what excitement can happen. Whereas most of Sinatra’s work is high-class, uptown sophistication backed by strict orchestration, this is one of the few records where his focused style is allowed to unleash against an adroit, swinging band. And here the band is allowed to shine as an equal participant as opposed to a backdrop for a superstar. Historically, this record also brought a younger audience to Basie in the 60’s after the era of Big Band had waned since the 30’s and 40’s. Featuring many standard songs, the record ends with a cool version of one of Sinatra’s hits I Won’t Dance.

Time Out – The Dave Brubeck Quartet, 1959

Time Out – The Dave Brubeck Quartet, 1959

Certainly you’ve heard the tune Take Five somewhere in your life with it’s 5/4 meter. According to Discogs website, “the album was intended as an experiment using musical styles Brubeck discovered abroad while on a United States Department of State sponsored tour of Eurasia, such as when he observed in Turkey a group of street musicians performing a traditional Turkish folk song that was played in 9/8 time, a rare meter for Western music.” This outing was also recorded at Columbia’s 30th Street Studio. I think the varying time signatures are what make this album so interesting and enjoyable. Although at times it is a bit jarring, it continually resolves and then dashes off again creating one of the most intriguing albums in all of jazz

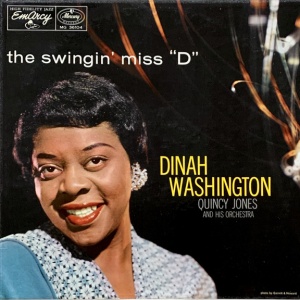

The Swingin’ Miss “D” – Dinah Washington with Quincy Jones and His Orchestra, 1957

Combine the bluesiest, most influential female voice of the mid-century with the talent of the bandleader who would later become one of the most successful producers of the late twentieth century and you get a 24 carat recording for the ages. One listen to Ev’ry Time We Say Goodbye or I’ll Close My Eyes and you can reach out and touch the heartbreak. Despite her tragic personal life (seven marriages) and drug overdose at age 39, her music is as enthralling and accessible today as it was in the 1950’s and early 1960’s.

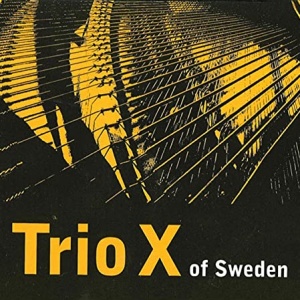

Trio X of Sweden – Trio X, 2005

Finally, we arrive at a more modern day take on the genre (similar to The Bad Plus). This trio, yes from Sweden, create breathtaking soundscapes. Another of their albums, Träumerei takes classical pieces and presents them in a jazz style. They are a recent find for me and I love their music. This early album of theirs is straight ahead jazz piano trio and varies the moods throughout the record. And the opening track Kavalaby is a particular favorite of mine as is the quiet Joel.

Now its your turn to start discovering this wonderful art. You can use this list as a jumping off point, and then see where the journey might lead you. If you have a particular favorite, or find something you treasure, please let me know in the comments.

Here’s the link to my Spotify Playlist of these records:

Thanks for sharing. Made me go and listen to Wayne Shorter’s Speak No Evil, a soundtrack someone else recently recommended. Several others were already familiar and heard often. I did look up Midnight Blue, which may have inspired several other musicians you did not mention.